Documenting Risk

Permanent link All Posts

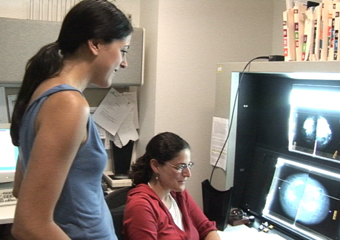

Joanna's sister Lisa, a mammographer, teaches Joanna how to read a mammogram. Photo credit: Ines Sommer

Joanna Rudnick doesn’t wake up every morning thinking, “today’s the day I will get cancer.” But the documentary filmmaker does live with the knowledge that she’s more likely to develop cancer than other women her age, in part because of her heritage.

The media first started linking Ashkenazi Jewish women with increased cancer risk in a National Institute of Health study released in 1995—nine years after both Rudnick’s mother and Gilda Radner were diagnosed with ovarian cancer. “In my mind, as a kid, 1986 was the year of ovarian cancer,” she says. “No one talked much about it before and suddenly it was on the cover of People magazine.”

Joanna, age 4, with her mother Cookie, an ovarian cancer survivor.

When she was 27, Rudnick had a genetic test that would shake her personal life to the core and shape her professional one. Her doctor told her that because of a mutation in her BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes, she has an 85 percent lifetime risk of breast cancer and a 60 percent lifetime risk of developing ovarian cancer. Compared with the general population’s 12 percent risk for breast cancer and 1 percent risk for ovarian, these numbers are staggering.

Rudnick began her personal process of dealing with the test result and the public process of making a documentary about women with BRCA genetic mutations. In the Family will air on P.O.V., PBS' award-winning independent non-fiction film series, on October 1 and Rudnick will appear as a guest on both John Callaway and Nightline in conjunction with the film's showing.

While far from a cancer diagnosis, a positive result leaves women with two almost unfathomable options: careful surveillance, which can leave some women feeling as if their body is a ticking time bomb, or the surgical removal of breasts and/or ovaries, which is physically and emotionally harrowing. Even though both options are frightening, Rudnick believes having a choice is better than not knowing. “It’s empowering to know that there are things you can do,” she says.

As Rudnick was weighing her own options, staying behind the scenes proved impossible. She had found support in a wonderful community of women—all races, mostly older, some with cancer and some without, all with BRCA gene mutations—but didn’t know another person in her situation: young, single, without children and hoping to have them. For her, surgery was off the table. To tell a full story, she had to include herself in the film.

“It sounds like sci-fi. To call a friend and say, ‘I have a BRCA gene mutation’ is weird. You’re not likely to hear, ‘oh yeah, me too.’ At 27 it separates you from your peer group and it’s overwhelming,” she explains. That gap in understanding, she hopes, can be bridged by communication. “We are moving in this direction [the ability to get genetic information] in public health and need to figure out how to create space and language for all of us dealing with a genetic predisposition,” Rudnick says.

Even as more stories are told, many women avoid getting tested because they fear the results or are concerned about insurance discrimination. A CNN/Time magazine poll found that 70 percent of respondents would not want to provide information about their genetic codes to insurance providers. While there haven’t been any lawsuits to date, there is no national law protecting people from genetic discrimination. “The fear really is insidious and keeps women from finding out,” Rudnick says. Both In the Family and its corresponding outreach program aim to quell such fears by empowering women with information. She knows firsthand how powerful information can be.

Rudnick never considered surgery when she first tested positive. But after connecting with other women, losing a friend to cancer during the filming process, and visiting another whose cancer has returned, she’s now open to the possibility. “Ovary removal after childbearing is probably an option for me in the future, but the decision is a process,” she says.

In addition to thinking about her future, Rudnick has been thinking a lot about her past. She says that looking at her family history and receiving support from both the Chicago Center for Jewish Genetic Disorders and the Jewish Women’s Foundation has connected her to her roots in a profound way. “I started thinking a lot about where I am from and who I am. I reached out to Jewish Women’s Foundation [for funding] because the population with BRCA mutations is full of pioneering Jewish women. We’re the first population going through this and can spearhead the education of others. I wanted to partner with the pillars of this community,” she explains.

When she thinks back to that 1986 People magazine cover, Rudnick recognizes the media’s power to connect with the public and get people talking. Documentaries like “In the Family” are vital because what you hear in a sound bite isn’t the whole story, and one woman’s story isn’t every woman’s story. For women to be empowered with choices, information must be accessible, health care providers educated and concerns about discrimination addressed.

More than any news article, her mother’s survival has influenced Rudnick. “My mom surviving ovarian cancer has strongly impacted the decisions I have made so far. The media often pits one choice against the other. Early on, surgery was seen as drastic and today it seems like that’s the applauded response. But living with the BRCA mutation is way more complicated than that. There’s no magic pill or easy way out,” Rudnick says, “but I am convinced that this knowledge saves lives and that’s very humbling.”

.jpg)