My journey through Jewish Morocco

Permanent link

The author in the northern city of Tangier, standing in front of a hotel with the Moroccan and American flags above the door.

Last spring, I attended a Havdalah service in Rabat, Morocco. The synagogue, tucked away in the second floor of a business building, was completely hidden from any and all passersby and, on the night I went, had more empty seats than occupied ones.

Halfway through the service, a cacophonous chorus of Muslim call to prayers went off, radiating from the loudspeakers on surrounding mosques and penetrating the sanctuary walls. The medium-pitched male voices reciting Arabic nearly drowned out the Hebrew prayers, as they do every Saturday. But the congregants, too deep in worship to notice, confidently carried on with the service.

During my time studying abroad in Morocco last year, I undertook a project that led me to immerse myself in the Moroccan Jewish way of life. I was unaware of Morocco's rich, deep-seated history of Judaism before going; this is a history that reaches back centuries, well before the wave of Islam swept North Africa in the seventh century.

At its peak in the 1940s, Jews in Morocco numbered 300,000, roughly 10 percent of the country's population (and more than any other Muslim country). Today, that figure has sunk to around 3,000, as many left to start new lives in Israel, Europe and North America, and that number is dwindling still. But after spending time with Moroccan Jews, observing their daily practices, visiting synagogues, and attending Shabbat services, Jewish concerts and a Passover seder, I found this small community to be very much alive.

Dates, fish and jam make up the recipe for Mimouna, an end-of-Passover feast unique to Morocco.

To get some background for my project, I spoke with a number of elderly Jewish Moroccans, listening to their stories about what it's like living in a Muslim country. One man told me that his best friend growing up was Muslim, and that they each participated in one another's religious practices, including helping prepare kosher food for holidays. A Jewish couple, though, said they experienced heavy anti-Semitism around the time of the Six Day and Yom Kippur Wars when tensions reverberated throughout the Muslim world and when many Jews left Morocco. Soldiers were sent to patrol the Jewish quarter where they lived and the couple nearly lost their jobs.

This got me thinking: why did some Jews stay when many of their friends and neighbors left? Again, the answers were all across the board. Some remained because of work, others because they couldn't afford the costs of travel, and others still because they felt a deep, personal tie to Morocco, their home. And because they chose to stay, I found, these people have no reason not to go about their lives as other Moroccans would. They work—as lawyers, teachers, politicians—maintain friendships with both Jews and Muslims and keep traditions. For the most part, they live happily.

A view inside the empty Benarroche Synagogue in Casablanca, just minutes before congregants make their way through its doors to pray.

But during a Moroccan Jewish concert in Casablanca, I caught wind of a trend that threatened to say otherwise. A Jewish high school student, who happened to be performing that evening, approached me and we got to talking. I remember him leaning in close, nearly whispering to me that he wants to leave for France when he finishes school, attend college there, and never return to Morocco. I asked why and he told me that there are hardly any Jews in Morocco so he has no reason to stay. Others confirmed what he said: Jewish youth are increasingly studying and living abroad, a trend that, coupled with the elderly passing away, could threaten the future of Judaism in Morocco.

Spending more time with Jewish Moroccans, I continued to sense the strength of their religious community but came to realize that, yes, it is in danger. What's worrisome is that Morocco is becoming like other Muslim countries, on the verge of losing evidence of its history of Judaism, of religious and cultural diversity. Unlike in the 40s and before, most Moroccans today don't know Jews simply because they don't come into contact with them.

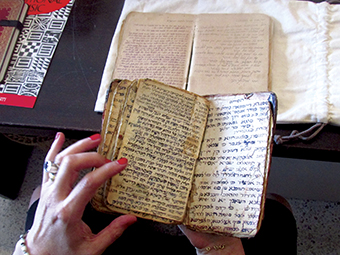

This personal prayer book was handwritten by a cantor in the 1920s. It now belongs to a scholar.

In the final few weeks of my program, I visited the Museum for Moroccan Judaism in Casablanca (unique to the Muslim world), as well as a museum in Fes, adjacent to an enormous Jewish cemetery. Both were stuffed with artifacts, clothing, photographs. These spaces reassured me that memories of Moroccan Judaism will remain for those who seek them out.

Just as it did for centuries, Judaism can and does exist in this country where Jews are a severe minority. After acquainting myself with the community, I hope it continues to exist.

Nathan Evans is a senior at Illinois Wesleyan University majoring in international studies and religion. A 2012 Lewis Summer Intern with JUF News, he currently works at the Kindling Group, a documentary film company in Uptown.

.jpg)