To Cut Or Not To Cut

Permanent link All Posts

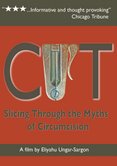

Cut, learn more at www.cutthefilm.com

I’m an avoider. My solution to the circumcision question (to cut or not to cut) is: I’ll only have girls. I am sure that this impractical resolution will result in a family of boys.

I would never even have been thinking about this question had it not been for Chicagoan Eliyahu Ungar-Sargon’s film, Cut . And he would never have been thinking about this issue if not for the time, at 15-years-old, he served as the Sandek, the person who holds the baby during the ritual, for his cousin’s bris in Jerusalem. He was appalled when the Mohel leaned over the baby and came up with blood on his beard. The image stuck with him and today, with Cut, he addresses the issue of whether or not to circumcise religiously, scientifically, ethically, sexually, straightforwardly and graphically through interviews with people from every perspective.

I admit I had to cover my eyes at a few points during the film. I had never seen a circumcision up close before. I had never even thought about it for more than five seconds before watching the film, but my screening prompted a long discussion among friends afterward–which, it turns out falls nicely in line with Ungar-Sargon’s goal of prompting conversation on the subject.

He judges the film’s success not on the number of minds he changes or how many viewers come away agreeing with him, but rather on the dialogues that viewers have after watching. He says this questioning and wrestling with ideas is really what being Jewish is about. After a screening, most stick around for an hour and a half or so discussion. After hearing lots of new information on a taboo topic, it’s only natural that people have questions as they’re processing the information.

Another documentary about circumcision was made in 1995 – Whose Body, Whose Rights – but it was clearly an anti-circumcision film. Ungar-Sargon wanted to make a documentary about his personal experience and viewpoints, while also including the perspectives of others. He tried to portray, “people who vehemently disagree with me in the most flattering light.” He also recognizes that the choice of whether or not to circumcise your sons is a very personal decision.

Ungar-Sargon’s interest in both film and circumcision began as a teenager, but these subjects didn’t come together in the form of Cut until years later. “The first time I saw film as more than just entertainment was in high school in Jerusalem, when I took a film appreciation class because I thought it would be an easy credit,” he says with a smile – it obviously became much more than that. But first he attended medical school for 3 years in England until he decided to venture out to pursue his true passion – film. When he applied to the Art Institute of Chicago, he says he had “never done anything artistic in my life, but I knew how to take pictures.”

Eliyahu Ungar-Sargon “cuts” right to the chase with his film on circumcision

Being raised in an Orthodox home, he DID have a lot of experience with traditional Jewish ideas and how they sometimes conflicted with modern society. One example marking clear conflict between Jewish and secular views is the role of women in traditional Judaism. There is much discussion on this topic and feminism in general, but with circumcision there is almost no discussion. People get uncomfortable questioning something that they perceive as being central or fundamental to being Jewish.

That perception is precisely what Ungar-Sargon wanted to focus on. Cut began in his documentary film class, and expanded into a feature film after he graduated. He and his wife, the co-producer, are now independently distributing the film.

Before starting work on the film, and before his experience as a Sandek, he wasn’t aware of all three steps of a traditional Orthodox Bris. Neither was I. Here’s how he explained it to me.

1. Milah – cutting of the foreskin

2. Pri’ah – removing of the translucent membrane

3. Metzitzah – suction of blood. Usually a sterilized glass tube is used for this step, but historically, and in more traditional movements, oral suction is performed. I won’t get into the controversy surrounding this step – that would have to be a whole separate story.

So the bris is a tradition going back thousands of years, but what about the non-religious reasons for circumcision? Here in the Midwest, 70% of men are circumcised, the highest rate in the United States. I recently heard a story on the radio talking about how circumcision can help prevent HIV/AIDS. Is that true? Ungar-Sargon’s research shows that these types of statements – circumcision can prevent _____(fill in the blank) - have been loosely related to the scariest diseases of the times. In the 19th century, circumcision was supposed to prevent epilepsy and masturbation (apparently considered a disease back in the day). In the 20th century it was linked to syphilis. During World War II, everyone entering the military had to be circumcised for sanitary purposes. Post WWII, it was supposed to prevent cancers, urinary tract infections, and now HIV. Over the years, scientific studies have disproved these connections each time.

That said, the film is not anti-circumcision and Ungar-Sargon doesn’t characterize himself as an anti-circumcision person (those who do prefer to be known as intactivists). The film offers every opinion from those of intactivists to those of a Rabbi who says it is an obligation. After a screening, some people leave no longer wanting to circumcise their sons while others leave with renewed conviction about the practice. Armed with new information, everyone develops her own personal decision.

Ungar-Sargon will continue in his goal to raise awareness and instigate conversation on difficult topics through film. Production of his next feature-length film documenting the Israeli-Palestinian conflict begins this November.

More information about Cut, screenings, and the DVD can be found at www.cutthefilm.com . Ungar-Sargon is also a guest lecturer in editing at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and teaches two classes – Masterpiece Cinema and Holy Athiesm – both available as podcasts on his site, www.eliungar.com .

.jpg)